HOUNOURS

Preisträgerin 2008

Siemens Music Prize 2008

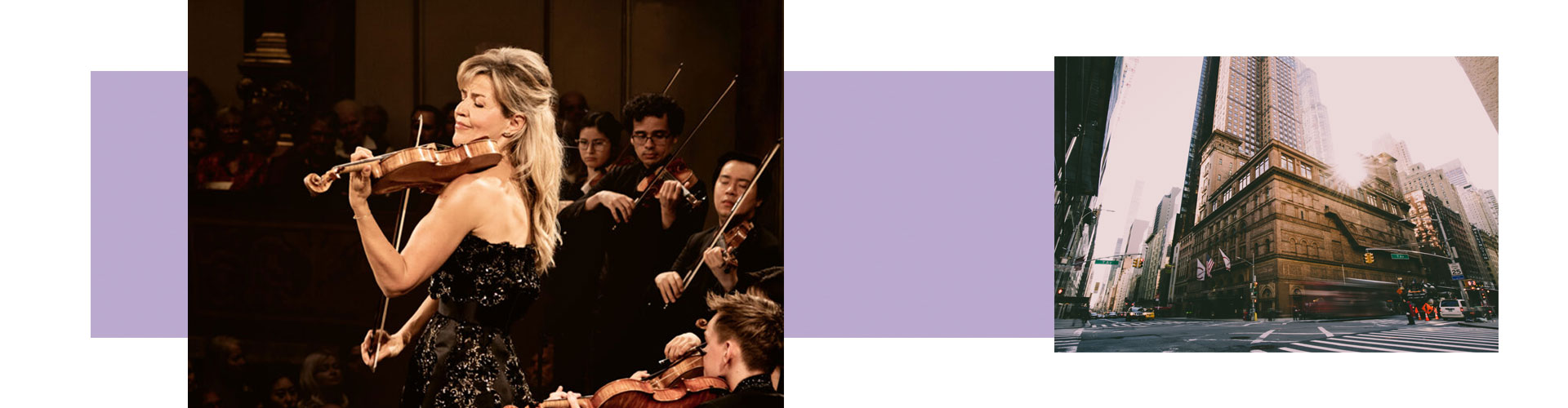

Anne-Sophie Mutter is this year’s recipient of the International Ernst von Siemens Music Prize, which comes with a cash endowment of 200,000 euros. The violinist is donating half of the prize money to the “Anne-Sophie Mutter Foundation”, which was officially recognized by the German government on July 7, 2008.The objective of the foundation is to further increase worldwide support for promising young musicians – a task which the violinist took on when she founded the “The Anne-Sophie Mutter Circle of Friends Foundation” in 1997.

Anne-Sophie Mutter is this year’s recipient of the International Ernst von Siemens Music Prize, which comes with a cash endowment of 200,000 euros. The violinist is donating half of the prize money to the “Anne-Sophie Mutter Foundation”, which was officially recognized by the German government on July 7, 2008. The objective of the foundation is to further increase worldwide support for promising young musicians – a task which the violinist took on when she founded the “The Anne-Sophie Mutter Circle of Friends Foundation” in 1997.

The Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts presented the coveted award to Anne-Sophie Mutter on April 24, 2008, at a ceremony in Munich’s Jugendstil landmark, the Münchener Kammerspiele. The eulogy was delivered by Joachim Kaiser.

The music prize, which is named after its creator Ernst von Siemens, the grandson of company founder Werner von Siemens, has been awarded annually since 1972 to a composer, performer or musicologist who has made an outstanding contribution to the world of music. The so-called “Nobel Prize for Music” continues to gain in international recognition with each passing year.

“Anne-Sophie Mutter is one of the few artists capable of blending talent, artistic character and naturalness with immaculate technique, inner feeling, emotion and reason. She plays with a unique warmth, soulful tone and direct expression of feeling combined with an impressive and frequently fiery temperament,” according to the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation press release the announcing the winner of the 2008 prize.

Laudatio Joachim Kaiser

Finally, Strauss ended up writing the script for his conversational opera “Intermezzo” himself. But Strauss knew quite well what he could and could not do. He therefore he sent Hermann Bahr the first hastily written draft of “Intermezzo” with the following cover letter: “Please read it and tell me honestly and without holding anything back what you think about it. One is a dilettante in all things that one has not managed to master since one’s 14th birthday.”

If the brutally descriptive comments of Richard Strauss were true, our colleges of music, if they were to focus solely on top performance, would not have to worry about overcrowding – at least in the fields of violin, cello and piano… A few decades ago Anne-Sophie Mutter said something even more radical to me in reference to the risk of getting a poor education when learning to play the violin: If you haven’t learned certain things by the age of 12 and have become accustomed to making certain mistakes, she said: “it’s all over.”

Fortunately, for Anne-Sophie Mutter it has never been over. In fact, things could hardly have gone better. She has been playing marvelously for years and has never had a need to adjust her style by as much as 100th of a millimeter to ensure that her sound alone creates sensuous joy in every receptive soul. Suddenly we knew not only who the queen of the violin was but also who the queen of heaven for her instrument was. But there is more that is truly and sustainably delightful: Anne-Sophie Mutter’s masterful, boundless virtuosity refutes any temptation toward seductive cultural pessimism!

She – as well as Gidon Kremer whom she highly regards – appeared to launch an era of great, masterly, expressive violin playing, thereby setting a shining example during the barren period following the deaths of Rubinstein, Serkin, Arrau, Kempff and Horowitz. It was a period during which opera houses struggled to find a suitable “Tristan”, “Siegfried” and “Lohengrin” due to, it appeared, a lack of directors of the caliber of Karajan and Bernstein. But her success is attributable not only to her exquisite artistry. It is also due to her character, to her curiosity, and to her rejection of self-satisfaction!

Thanks to the fantastic depth of her intonations, she also motivates composers. A few representative names are to be mentioned here: Wolfgang Rihm, Witold Lutoslawski, Henri Dutilleux, Sofia Gubaidulina. They, and many others, have dedicated their important works to her!

An artist cannot “plan” such effects. They emanate from the artist’s being, power of fascination and character. Suddenly the music scene is teeming with young and very young violinists, who appear to be inspired by a desire to achieve a high degree of artistic expression rather than striving for virtuosity for virtuosity’s sake or driven to perform Paganini’s capriccios better than Ricci, Accardo or Haifetz. It is precisely Anne-Sophie Mutter’s aura, which has contributed significantly to the era of Frank Peter Zimmermann, Vadim Repin, Maxim Vengerov, Hilary Hahn and Julia Fischer. What’s more, we appear to be entering a golden age of remarkable young string quartets.

I spoke here of Anne-Sophie Mutters “character”, which has had far-reaching effects. But what exactly does “character” mean? We need to be more precise here – especially in view of Clemenceau’s contemptuous but illuminating observation that “if anyone has any character at all, it’s usually bad.” But for Anne-Sophie character is something much more compelling – it is expressed as her inner ambition. Those who are allowed to observe her up close can feel it. Her entire inspiration comes from a compelling inner – and not an external – ambition, which emanates from a kind of despair – and thus the despicable abandonment of all inner ambitions.

Let us take a look at what is behind the legends that attribute her career to “plain luck.” I was very fortunate to be present when Anne-Sophie Mutter performed her first orchestra rehearsal with Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in Salzburg on June 27, 1977. There sat the inside favorite, a still somewhat chubby 13-year-old teenager in blue jeans and with a harmlessly old-fashioned hairdo. Karajan wanted to introduce her to the world. She was very aware of was what on the line. But she had to wait her turn. Up until the lunch break the maestro experimented with “Zarathustra”. A complicated work. Then came the “Jupiter Symphony” performed by a downsized orchestra. Anne-Sophie Mutter sat patiently waiting for hours. Waiting for what must have seemed like eternity. Hardly an envious situation. Finally, it was her turn. And Karajan demonstrated his gentle and caring expertise. The wait must have been excruciating for the soloist. But now Karajan showed that he emphasized with her. He interrupted the Berlin Philharmonic while the orchestra was playing the prelude to the concerto in D major. He pointed out a small mistake, which was perhaps not really necessary. Suddenly Miss Mutter was completely relaxed. She saw that it was possible to make mistakes during a rehearsal like this. That it is possible to be interrupted. This was the encouragement she needed. Mozart’s magic transcended through the just and unjust. No sound was indifferent; each was equally internally illuminating.

But what came next? It was the arduous test of the true durability of one’s “inner ambition”, which consists of how one copes with defeat following a triumphant beginning. Only when this happens – and such setbacks permeate every artist’s biography – only when this happens is one’s spiritual physiognomy finally formed. Anne-Sophie Mutter herself said what Karajan expected from her following that brilliant Mozart beginning. Karajan suggested that she perform Beethoven’s violin concerto one year later.

The successful 15-year-old did her best. For a half-year she studied for the famed concerto with instructor Aida Stucki, a student of Carl Flesch. She then described what happened with unabashed candidness, whereas others prefer to conceal such defeats out of embarrassment: “I then traveled to Lucerne as planned to perform Beethoven’s concerto for Karajan.” Karajan was extremely busy. She continues in her report: “But after the introduction” – thus after the grand solo – “he said gruffly: ‘Go home and come back next year.’” She writes further: “A year later things went a bit better, and we worked constantly on the concerto between his rehearsals and concerts.” By the way, she always chose to finish Beethoven’s concerto with a 70-second, stunning virtuosic Kreisler cadenza, which, at the half-way point, become a fast-and-furious passage orgy. Karajan was proud of his violin genius in both a fatherly and sporty way. In Japan I observed how he beamed with pride as he saw how damned independent his creation had become when Anne-Sophie Mutter, to the astonishment of the Tokyo audience, launched into the explosive the cadenza with which he described as “breakneck speed”.

Whereas Karajan was her discoverer, another great musician, namely Paul Sacher, became increasingly important to young Anne-Sophie Mutter as a music teacher and mentor with respect to her relationship with exquisite contemporary art. I met and learned to admire this great and generous Swiss conductor, patron and inspirer of a multitude of modern works, here in Munich in conjunction with the Siemens Music Prize. At that time both he and I sat on the very first Siemens Music Prize jury. His advice and his suggestions carried weight. I also had the honor of being invited to his home in Basel. This was in every respect one of the noblest experiences of my life.

Just how important Paul Sacher was for Anne-Sophie Mutter’s relationship with contemporary composers is evident in many ways. For example, Witold Lutoslawski composed his Dialogue for Violin and Orchestra – “Chain 2” – for Paul Sacher, and recommended that Lutoslawski direct the premier performance with Anne-Sophie Mutter playing the solo. And he was so thrilled with her interpretation that two years later he reinstrumentalized his “Partita” in 5 movements as a violin concerto and dedicated it expressly to “Anne-Sophie Mutter.” Her relationship with the nocturne “sur le meme accord” by Henri Dutilleux developed in much the same way. Anne-Sophie Mutter totally adored his compositional integrity and considered him absolute best. The composer once remarked: “The relatively short work is dedicated to Anne-Sophie Mutter, to whom Paul Sacher introduced me some 15 years ago.”

Ladies and gentlemen – as an older music critic one tends to be skeptical of certain specialization trends. When I hear that this or that violinist or pianist prefers to play only contemporary works or only round-bow baroque solo sonatas, one has to ask whether this is a totally voluntary limitation. But Anne-Sophie Mutter has no need for such alibis when it comes to her approach to contemporary violin literature. Quite the contrary. As the masterly, exemplary and adventuresome interpreter of great traditional works from Vivaldi to Debussy, Anne-Sophie Mutter has no need to fear the competition.

I am so grateful for the memories as I think back on the many opportunities I had in Munich and other places to experience her performances of Brahms’ violin concerto in “live” concert. To me they seemed more impressive than the performances of even the likes of David Oistrach, Nathan Milstein or Itzak Perlman – not to mention lesser gods. Her performances were spiritually overpowering experiences. To find something comparable I have to go back to Hamburg in 1948 when 29-year-old Ginette Neveu moved me with her highly dramatic Brahms interpretation. Such performances are more than simply good or very good concertos. They extend light years beyond the bounds of the usual, the beautiful, the ordinary. My friend Stephan Sattler summed up his experience upon seeing Anne-Sophie Mutter perform Brahms’ sonatas here in Munich as follows. He said that he could hardly believe that Germans were still capable of producing such a wondrous creature of such absolute coherence. There was so much passion, stylistic confidence and freedom expressed that evening in Anne-Sophie Mutter’s artistry. She never gives the impression that rehearsing and performing contemporary works is merely a magnanimous, required exercise. My colleague and friend Harald Eggebrecht, who published a splendidly knowledgeable book about the “Great Violinists” expresses it in this manner: “Her experience with newer music has significantly expanded Anne-Sophie Mutter’s interpretive horizon. She can now let her sound turn ashen pale; she does not shy away from harshness or even ugliness.”

It is certainly impressive: the diversity of the expressiveness, the various intonations, the mysterious lack of authenticity, as Anne-Sophie Mutter senses and fulfils the exciting, breakneck high drama of the extremely important violin concerto of Sofia Gubaidulina composed in 2007. The work bears the enigmatic title “In tempus praesens”. She begins the recitative initial solo of the concerto with both wonderful timidity and oppressive expressiveness. The music is not directly contemporary but as if someone is thinking or dreaming behind a curtain and now and then glances into the promised land of the expressivo.

What inner subtleties. But the most violent passage – for both the composition and the interpretation – is yet to come. The last minute before the cadenza. The composer and the orchestra rise to thundering anapestic short-short-long rhythms – while the solo violin fights violently for its life against this chord. This passage offers drama comparable with the ecstasies of the main movement of Brahms’ violin concerto. A great actress with unlimited adaptability would not be able to follow such multifariousness more captivatingly than Anne-Sophie Mutter.

Having just offered some admirable comments about the remarkable interpretation of Sofia Gubaidulina’s second concerto by Anne-Sophie Mutter, there are some more notable aspects that need mentioning here. The wonderful, painfully flowing sound she elicits from Lutoslawski’s “Partita” largo and how she transforms it into a differentiated “cantabile” experience. How she honestly and discreetly masters Dutulleux’s “Nocturne” with such restrained legato. What brilliant weapons she has in her arsenal which she draws upon in violinistically and spiritually conquering Penderecki’s “Metamorphosis.”

And in daring to make a wild comparison: She plays with a modern and always smooth violinistic style. Milstein once performed Bach’s solo sonata and partitas with wonderful expression and deep meaning. He was able to truly and reverently marry Bach and Sarasate. In this same manner Anne-Sophie Mutter succeeds in achieving a natural blend of tricky modernism and violinistic ecstasy! This is by no means simply a sure-fire attitude of a world-class soloist – but rather a virtually endless but always new, surprising abundance of tenderness, aggression, modification.

I know from her personally how she likes to avoid constant uniformity and identical repetition. It thus appears absurd when soloists, in performing a classical sonata movement, resort to certain ritardandos – as if every sound, every expression was meant to be articulated in the same identical manner. No mortal always utters the phrase “I love you” exactly the same every time. Instead the phrase is repeated sometimes with more passion, sometimes with a touch of boredom. But not always the same. Anne-Sophie Mutter takes this modification obligation to its utmost: “I rely entirely on the moment whereby the bow-phrasing always remains the same. As a string instrumentalist,” she continues, “you can achieve new coloration through fingering. In the reprise I always employ different fingering – even it its northing more than a different gesture than the one used in the exposition.”

As laudator I can only view such details with total amazement. But I must add that there is awesome concentration concealed behind such meticulousness and perfection. This apparently effortless virtuosity is built upon blood – upon the demands which the artist has placed upon herself! Most recently, following the premier of Jan Schmidt-Garre’s wonderful film about Anne-Sophie Mutter’s encounter with the Gubaidulina’s second violin concerto, the artist said that the comments of the composer about her interpretation are the real acid test. The severest judgment of everything that she does!

It now becomes clear why many great artists consider quitting at the pinnacle of their outstanding careers and celebrated successes. Ten years ago Anne-Sophie Mutter was playing with just such an idea: “I plan to retire when I reach my mid-forties”. And she added: “Perhaps I’ll then take up conducting.” Today the notion of being able or wanting to quit is an essential component of every exceptional career. Not as a definite decision but rather as a consolation, as a vision of freedom, as a means of alleviating stress. How would it be if we were to ask our Anne-Sophie Mutter to take 45, a number she equated with the end of the line, and transpose into 54! And when she then reached 54, to convince her to double the original 45! That would come to 90. And what were to happen after that would no longer be our earthly concern.

Dear, Anne-Sophie Mutter, I congratulate you upon winning the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize. It is an expression of how much the music world reveres you and your musical talent. It also an indication of how much we all need your artistry and could not bear to be without it. Thank you very much!

Joachim Kaiser

A word of thanks

Dear honored trustees and members of the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation, dear Professor Kaiser, I am simply overwhelmed by the honor and recognition that you have conferred upon me.

When I learned that I was to receive the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize, I felt ashamed. I was ashamed, honorable Sofia Gubaidulina, because I was to receive this exalted, globally recognized prize from you. A feel deeply honored by your presence here this evening. Your concert on Monday in the Allerheilige Hofkirche was a glorious moment. And my admiration for the great composers goes hand in had with my admiration for the interpreter Sofia Gubaidulina.

To see my favorite composers here today is a special honor that gives me great joy.

I can hardly believe my eyes as I look around this hall. Only in my fondest dreams could I ever have imagined to see wonderful Maître Henri Dutilleux seated next to Sofia Gubaidulina.

Très cher Henri, je suis très fière et éternellement reconnaissante que vous soyez venu spécialement de Paris pour être avec moi. Je vous admire depuis la première note que j’ai entendue de vous.

It is also with great pleasure to see another great Wolfgang, after Wolfgang Amadeus, namely Wolfgang Rihm. I also thank you from the bottom of my heart for honoring me with your presence.

And here straight from New York are André Previn and Sebastian Currier. André, you dedicated one of the most beautiful violin concertos to me. My movement, the third, based on a popular children’s song, is always a trip in time through my childhood.

Sebastian, I can’t wait to premiere the concerto Time Machine that you wrote following your inspiring Aftersong, which we will hear tonight.

Dear members of the curatorium and foundation council, your award fills me with pride and joy as no other award before it has.

And as if the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize did not bring me enough joy, you, my dear Professor Kaiser, have honored be with your poetic words. In view of your outstanding linguistic talent, I will not even dare to attempt to express my thanks in words. Because I am certain, my dear ladies and gentlemen, that the voice of my violin will bring you greater pleasure.

But first I would like the share with you my thoughts on the necessity for privately sponsoring the arts. It now appears pointless to complain about the lack of political support for the arts when it comes to dividing up the public financial pie. The focus of public funding is now on basic necessities, and there does not seem to be much left for allegedly peripheral projects.

What remains is hope. The hope that we can establish a bridge, which at first glance perhaps appears to be self-contradictory, namely bridge between the worlds of business and private sponsorship and the world of culture. In 1935 the unforgettable Paul Sacher wrote the following words in his essay “Culture and Crisis”. I quote: “Because engaging in any form of the arts requires a certain material basis, and, for example, because composing and performing music always cost more than the amount of money they generate, the inherent affinity between the art and crisis is self-evident.” The economic crisis of the thirties, which formed the background against which Paul Sacher wrote these words, has fortunately long past. But the necessity for providing a material basis for all forms the arts transcends all economic ups and downs. Musicians have long not been satisfied with simply eking out a living through the performance of their art. Much more important is that they be afforded dignity and artistic freedom.

This is especially true for composers – even when they enjoy the highest degree of recognition and fame. Two examples: Karlheinz Stockhausen, the 1986 recipient of the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize, said in accepting the award: “When I received the letter from Dr. Sacher … I was thankful and greatly relieved. Over the last few years, as the result of artistic recklessness, I spent much more money than I possessed for printing my scores and for the royalties, which the ‘new team’ at Deutsche Grammophon demanded that I pay to performers and broadcasters for the release of the recordings of my works.

And Wolfgang Rihm, for whom my respect has no limits, said here in 2003: “A composer lives from day to day. When be begins to compose, a composer must either have received an inheritance, which is not my case, or he must pay an enormous amount money out of his own pocket. I am therefore thankful that I finally have a means to pay off my debts.”

Ladies and gentlemen, the two composers I mention here are only the tip of the iceberg. Without support, whether through prizes, stipends or commissions, the majority of avant-garde musical creations would simply not exist!

My dear honored trustees and members of the Music von Siemens Foundation, as a performer I am dependent upon the work of composers. I have thus long felt a deep debt of gratitude to them and them alone for their exemplary and courageous support for contemporary music.

The public has rarely conferred upon these prize winners the respect that they deserve. I would therefore like to again draw attention to the distribution of prize money between the music and support prizes. Ninety-one percent of this year’s total prize money has been allocated to the support prizes, and it comes to the proud sum of 2.1 million euros. This amount has been steadily growing for some time. The Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation is thereby not only rewarding the tip of the iceberg but is lending exemplary support to the education and training of young artists. For this reason I feel deeply indebted to you!

The urgent need for supporting talented young artists is something that I experienced myself while growing up. I know how difficult it is get the necessary support during these important formative years. I had the good fortune of working together with great musicians during my early years. Thanks to them I was able to grow as an artist. I have very fond memories of my wonderful mentor Aida Stucki. She remains a guiding star for me today, and we remain very close friends. And I had a tremendous opportunity to be allowed to audition before Herbert von Karajan.

And then there is Paul Sacher, who was a tremendous supporter and patron during my early years and who helped me develop my passion for modern music. The premiere of Witold Lutoslawski’s Chain II, which he directed in 1986 in Zurich, was the beginning of a new era for me. It opened my ears to an entire new universe and has made my life as a musician much richer than it would have been if I had only focused on the existing repertoire.

Every premiere is the equivalent of an artistic rebirth. Every new work poses new questions, has its owns limits of understanding and its own technical demands. But every new work is a living dialogue with the composer. And I admit that during such conversations I very rarely have an opportunity to express my own point of view.

In all of the years of my youth there was only one work that I could not relate to, namely Berg’s “To the Memory of an Angel.” He dedicated it to the daughter of Alma Mahler, who died of polio at an early age. It requires a real birth – that of my daughter and later my son – and the ecstasy connected with it to make the deep despair over the loss of child comprehensible. And thus every premiere, every moment of happiness in my life as well as the difficult days of my Seelenlandschaft would become increasingly more similar to a picture by Mark Tobey. His paintings, with their very beautiful Japanese ceramic tiles with all of their cracks, appeared to be a likeness of my increasingly more porous soul.

Perhaps this maturization process made me a better musician – deeper and more precise in one respect but freer in another.

In past years I have attempted to pass on to the next generation at least a little of the happiness that I experienced very early on. This is possible only with collective support – especially in view of the financial dimensions involved. For this reason the Anne-Sophie Mutter Circle of Friends Foundation was founded 11 years ago. In order to increase the level of support, a foundation parallel to the Circle of Friends is now being established. I will now allocate the 100,000 euros that comes with the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize to this foundation.

Ladies and gentlemen, I cordially invite you all to contribute your support. Because we can succeed only when we all take an active role in supporting talented young artists. This is a tremendous challenge for all of us who care deeply about the future of music. In order to help them I also need your help. Please lend us a hand so that every extraordinarily talented musician has an opportunity to open a window to a higher dimension for all of us.

We support young musicians financially by helping them obtain suitable instruments, by granting them scholarships and by arranging instruction from renowned musicians or auditions before outstanding directors.

We are thereby pursuing a very new and, to the best of my knowledge, a very unique course in that we are commissioning composers to compose works for us. We are expanding the repertoire for these scholarship holders while at the same time deepening their interpretive capacity. It was Roman Patkoló, a talented contrabassist, who was responsible for launching us on this course. Virtually no soloist repertoire existed for his instrument – until April 14th of last year. It was on this day that the Double Concerto for Violin, Contrabass and Orchestra premiered in Boston. This enchanting work was composed by Sir André Previn at the behest of the Circle of Friends Foundation.

More contracted compositions are now being composed. For example, Kristof Penderetzki is currently writing a composition for violin and contrabass, and Wolfgang Rihm is composing works for Roman and me.

Ladies and gentlemen, honored trustees and members of the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation. Because music says more than a thousand words, it is now time for us to enjoy that which brings us all here in the first place – namely music, with which I would like to thank you all from the bottom of my heart.

Although you are rewarding me today for what I have accomplished in the past, I view today above all as constant future challenge.

You will now hear Mikhail Ovrutsky accompanied on the piano by Ayami Ikeba. Mikhail is also a Circle of Friends scholarship holder. In addition to performing as a soloist, he is employed by the Beethoven Orchestra in Bonn as first concert-master and by the Cologne University of Music as a lecturer. He is a fantastic violinist who has performed Bach’s Double Violin Concerto in many European countries.

Afterward Roman Patkoló and I will play the cadenza from the Double Concerto for Violin, Contrabass and Orchestra by Sir André Previn.

For me the high point of the evening will be André Previn’s improvisational artistry on the piano. There is nothing that gives me more pleasure, my dear André, than listening to you improvise. I like to listen most of all to celebrated American theater music reinterpreted by you.

I thank you for your attention.

Anne-Sophie Mutter