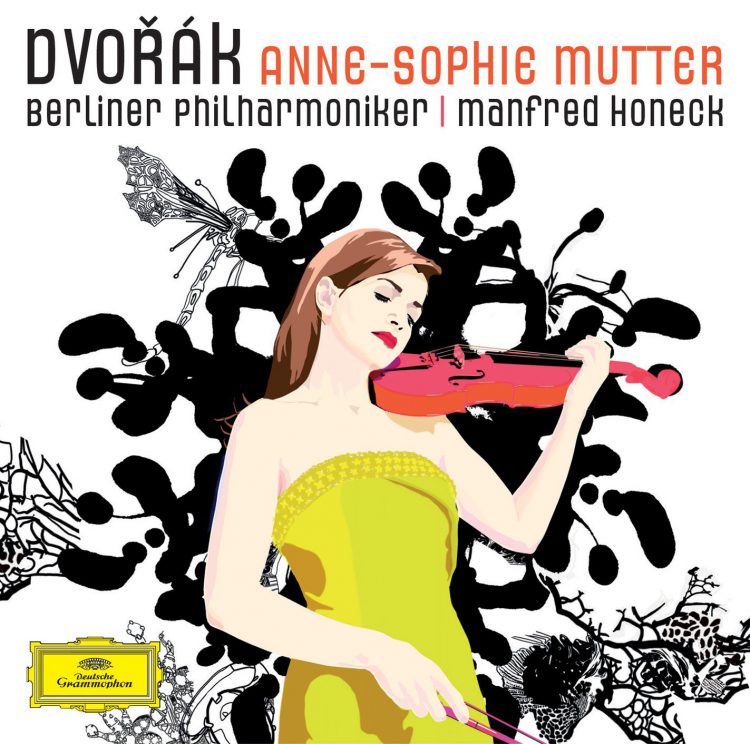

Together with conductor Manfred Honeck and the Berlin Philharmonic, Mutter has made her debut recording of Dvořák’s Violin Concerto – a voluptuous and emotional work of the high-Romantic era. “It’s wonderful to encounter an orchestra and conductor where something happens as soon as you start playing together. When I work with the Berlin Philharmonic and Manfred Honeck, I can feel a creative tension between us that motivates, inspires and uplifts us all,” says Anne-Sophie Mutter.

She and the Berlin Philharmonic recorded their first album together in 1978, not long after Herbert von Karajan had discovered the young violinist. He knew that Anne-Sophie Mutter and the Berlin Philharmonic would be natural collaborators because they shared a musical identity and an understanding of high-quality music-making. Thirty years on (their 1983 recording of Brahms’s Double Concerto was the last they made together), that shared musical philosophy still underpins the way they work together.

For Manfred Honeck, therefore, it made perfect sense to reunite two classical soulmates for this recording of Dvořák’s Concerto. “Anne-Sophie Mutter’s playing is distinguished by her colouring and her virtuosity. She surprises you again and again. Technically, she is certainly one of the world’s best violinists,” says Honeck, who recognises similar characteristics in the Berlin Philharmonic. “Just like Anne-Sophie Mutter, they can create any sonority and play at any tempo with no loss of quality. So when she performs with the Berlin players, you can immediately sense that very special energy between them. In Dvořák’s Violin Concerto it created an almost liturgical, sacred atmosphere.”

Even an orchestral generation after their last joint recording, there are still members of the Berlin Philharmonic with first-hand memories of Anne-Sophie Mutter’s early days. One such is the horn player Fergus McWilliam. His first experience with Mutter was a concert of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. “That was in 1987,” remembers McWilliam. “Herbert von Karajan conducted the orchestra from the harpsichord. Back then, the Philharmonie concert hall was only about twenty years old, and, as usual with Karajan, the orchestral forces were enormous. The musical spirit that radiated from this young violinist was unbelievable. Anne-Sophie Mutter had both a natural, primal energy and incomparable technique. When she came back to record the Dvořák, it was amazing to see that she still has that exact same energy today.” McWilliam also thinks Anne-Sophie Mutter and the orchestra have come full circle with this new recording: “In her early performances with us she was still thought of as a child prodigy; now we’re admiring a mature artist, one who knows exactly what she wants.”

Many other former associates and colleagues of the violinist now play with the Berlin Philharmonic. Among them is violinist Christoph Streuli, who studied with Anne-Sophie Mutter. He says: “What’s special about Anne-Sophie Mutter is that she is an outstanding live artist. She puts her all into every single phrase and can sustain new, overarching themes for long periods, sweeping an orchestra along with her.”

Anne-Sophie Mutter has been playing Dvořák’s music for decades. Programmed with the Mazurek op. 49, the Romance op. 11 and the Humoresque op. 101 no. 7, the Violin Concerto forms the centrepiece of the new album: “For me the occasion to make this recording, musically speaking, was overdue, because I’ve worked intensively on this piece. I went back to the orchestral score and revised almost everything that I’d done previously: the fingerings, the bowings and the phrasings. So it really was high time I recorded the Violin Concerto.”

Dvořák began composing the concerto in 1879 at the suggestion of his publisher and finished it two years later. The piece was a challenge for the composer, and he sought advice from Joseph Joachim, star violinist of his day and close friend of Johannes Brahms. He sent Joachim the score for revision, but the two of them did not see eye-to-eye on the work. For Anne-Sophie Mutter, this problematic collaboration between composer and violinist is one of music history’s missed opportunities: “Dvořák had probably hoped that he could develop as close a relationship with Joachim as the one the violinist had with Brahms. But for unknown reasons the two never found any common ground.” Mutter herself would love to have been able to reply to Dvořák personally. “Thanks to email I’d definitely have been able to react quickly too,” she says. “But of course I don’t know if our collaboration would have been any more fruitful.”

Dvořák certainly seems to be the perfect choice for Anne-Sophie Mutter’s return to the studio with the Berlin Philharmonic. Their performances of his music highlight once again the mutual trust and shared musical traditions that bind them together. Past and present meet, to wonderful effect, in this magical reunion.

Axel Brüggemann

August 2013