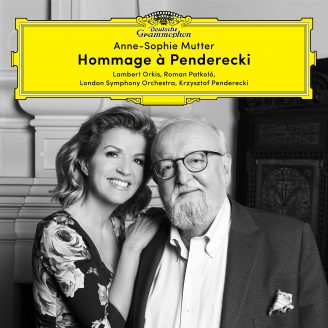

Even at the age of eighty-five, Krzysztof Penderecki’s thinking has lost none of its self-critical impulse of earlier decades. His technical assurance must have increased – indeed, it must now be immense, otherwise it is impossible to imagine how one of the greatest living composers could have produced such a vast output that includes masterpieces such as Anaklasis, the Stabat mater, the St Luke Passion, stage works such as The Devils of Loudun and Paradise Lost, symphonies, concertos and chamber music. The products of a universal mind that ranges far and wide over every genre command such awe and respect that it seems almost absurd to think that they may be the result of an effortful process accompanied by self-doubt. And yet there is no doubt that with time Penderecki has also placed greater demands on his own creativity and felt a greater sense of responsibility. “Compositional phases are days of self-doubt and even despair. You strike out in completely different directions, including ones that are entirely wrong. You move as if in a labyrinth. In Lusławice, which is where I live, I have planted just such a labyrinth. It is so big that I sometimes lose my way in it and as a result can’t immediately find my way out again. I find this tremendously fascinating. Whenever I write a larger piece, I have the feeling that I am moving around in a labyrinth like this. I advance, branch off to the side and then retrace my steps. I am searching. And ultimately it is exactly the same with composition as it is with the labyrinth: there is only one way back, and this is the best solution. This is the solution that you have to find.”

Krzysztof Penderecki’s Second Violin Concerto, which he completed eighteen years after his First, creates the impression of a vast labyrinth which, not in the least sinister, is as fascinating as it is magnificent. In his First Violin Concerto Penderecki had turned his back on his radical avant-garde and experimental works of the 1960s and consciously set out in search of the musical idioms of the 19th and early 20th centuries as found in the great violin concertos from Beethoven to Berg. The Second Violin Concerto is more obviously a synthesis of the very different stylistic directions that he had explored over the previous decades. Himself an excellent violinist, Penderecki began work on the score in 1992 but it was not until the Saturday of Holy Week in 1995 that he completed it in Kraków after a series of lengthy interruptions. It was dedicated to Anne-Sophie Mutter, who performed it for the first time later that year.

Composer and violinist had first met seven years earlier. It was a meeting that Penderecki himself described as a “shock” but which was to lead to a hugely productive artistic relationship between them. Penderecki had conducted Prokofiev’s First Violin Concerto at the 1988 Lucerne Festival, when the soloist had turned out to be a fifteen-year-old girl who had electrified him from the very first moment. “Before me stood a child with a violin, yet she played like an adult, actually better than an adult, because it was fresher. From the outset Anne-Sophie had a very special quality that is hard to describe. The way she played was fantastic, but above all it was her interpretation that was fantastic.” It was then that Penderecki conceived the desire to write a piece for this young and exceptional violinist, a desire that led to the composition not only of the Second Violin Concerto but of three other works, all of which are included in the present release. The title Metamorphosen came to Penderecki only at the end of the lengthy creative process when it became clear to him how central to the work is the idea of transformation. The concerto consists of a single large-scale movement laid out along powerfully symphonic but at the same time rhapsodic lines. As a piece it is full of contrasts, ranging from the touchingly calm and heartfelt to outbursts that are wild and rhythmically complex, while being propelled forward by a remarkable motoric energy. A great solo cadenza affords the performer every opportunity to display her virtuosity before the solo writing is once again integrated into the symphonic action and the concerto dies away in a meditative cantabile passage. As the composer says, he was always aware of the performer for whom he was writing the work, but he cannot have known that at the time she received the concerto, Anne-Sophie Mutter would be undergoing one of the most difficult periods in her life: “My husband died only a few weeks after the first performance. He was already ill when I began to study the piece, which has an incredible depth for me. Metamorphosen caused something to resonate in me, while helping me to understand the transformation from the here and now to another dimension and perhaps also helped me to process that experience. That is why it occupies a special place in my life. More generally, it is far more than mere admiration that has bound me to Krzysztof Penderecki’s works for several decades. I am shaken to the very roots of my being by the depth of emotion that issues from them – almost more than I am by his genius as a composer.”

This is also true of Penderecki’s Second Violin Sonata, which was composed in 2000. It too was written for Anne-Sophie Mutter and dedicated to her. This great multilayered work lasts a good thirty minutes in performance and constitutes a dramatic disquisition on life in all its facets. At the end, when the wonderful theme of the third movement returns like an outcry of indignation, the work comes full circle, leaving audiences and performers alike deeply shaken. “For me,” says the violinist, “this music tells us so much about this great artist and his soul. There is a quite unique quality and depth of expression that not every work of music possesses – certainly not in the present day. I regard this as a great gift!” Penderecki himself is fascinated by the way in which a work like this can develop a life of its own in the hands of its performers. “It may sound strange, but ultimately I doubt if you really understand your own music. You write and write. Only when you hear the music – or hear it as Anne-Sophie plays it – do you really understand it. It was never originally intended to be a dramatic work, that’s not what I’d planned. But that’s what it turned out to be.”

Lasting around twelve minutes, La Follia for violin solo dates from 2013 and in Anne-Sophie Mutter’s view has something “labyrinthine” about it. We might imagine a homage to Penderecki’s great Baroque forebears, an idea that is by no means absurd when we recall that Penderecki sees in Bach “the greatest God, without whom I would not compose”. At all events this ninefold reworking of the theme of a Baroque sarabande, with its elaborate set of variations, may be heard as a profession of faith in the history and tradition of which Penderecki continues to be an active part. It goes without saying that he wrote the piece with its dedicatee in mind. First performed in December 2013, it makes the greatest of virtuosic demands on its interpreter. Indeed, its very title might allude to these insane “follies”. Even Anne-Sophie Mutter admits to pouring out her heart to the composer and complaining about a number of intervals that were simply unplayable. But it is very much these difficulties that attract her: “Time and again a contemporary work opens up new possibilities and allows you to discover new things, new tone colours, technical demands that I didn’t know existed. Without this my life would be poorer. I’d miss this particular intellectual challenge.”

Whereas La Follia is a great monologue, the Duo concertante that Penderecki wrote for Anne-Sophie Mutter and Roman Patkoló in 2010 pursues the idea of a musical dialogue. Here we are party to an amusing conversation between two people tossing their ideas to and fro, avoiding one another, falling silent and either allowing the other person to speak or else listening to them.

Concertos, sonatas, solo works and duets: these are all examples of the classical forms within whose circumscribed limits Krzysztof Penderecki – one of the great figures of our age – operates, while continuing to expand those confines. “I’ve been writing music since I was six. I’m now almost eighty-five. What is so wonderful about writing music is that you can keep on creating something new, above all for such a wonderful violinist as Anne-Sophie Mutter. You then feel like seeking out new paths – and finding them. With each new work I start from scratch and think first about questions of form. Of course I can write notes. But I like to find forms and turn these into something that hasn’t previously existed – that’s the challenge I set myself. Ultimately, however, all forms are basically classical forms. There aren’t any others.”

Oswald Beaujean, Translation: texthouse

June 2018