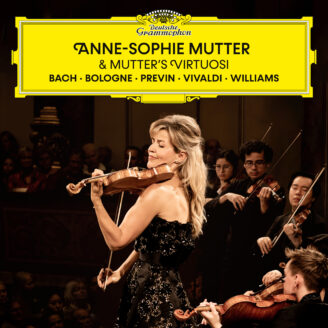

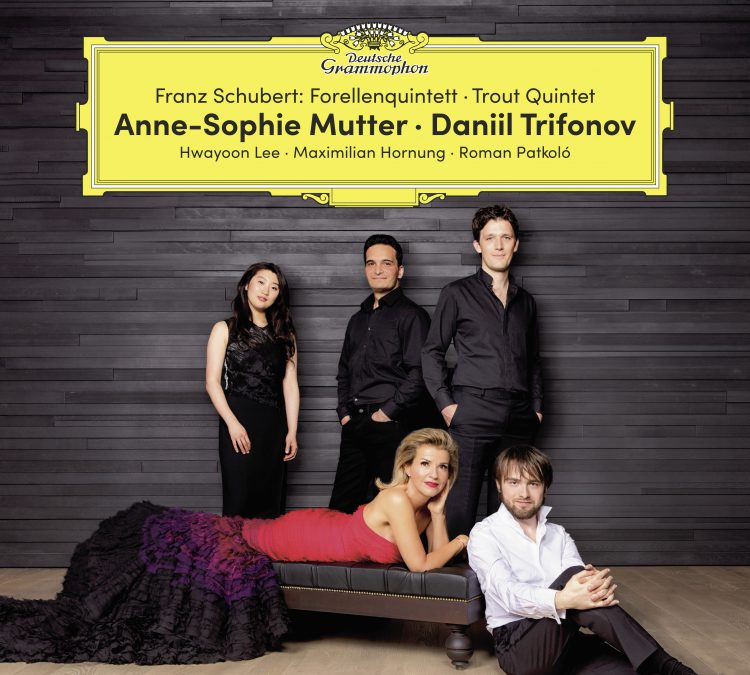

Schubert’s “Trout” Quintet, with its unusual scoring and easy-going levity, is one of his most beautiful creations in the realm of chamber music. Of course, one must be careful not to mindlessly link Schubert’s life and the music he wrote at the time. But the “Trout” Quintet cries out for such links. Though he only completed it in Vienna in autumn 1819, it is the fruit of an obviously carefree holiday that he took in Steyr that summer at the age of 22, together with one of his closest friends, the baritone Johann Michael Vogl, who was born in Steyr. Schubert’s letters wax ecstatic about the magically beautiful landscape and eight charming young ladies (“nearly all of them pretty”) in his immediate surroundings. His domestic concerts at the home of the enthusiastic amateur cellist Sylvester Paumgartner, in a circle of close friends, brought him attention and recognition. Finally, it was Paumgartner who commissioned him to write a quintet with the same scoring as Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Piano Quintet op. 87, namely, with a double bass instead of a second violin. His patron also expressed the wish that it include his favourite song, Die Forelle (“The Trout”). Schubert fulfilled this request by inserting a set of variations, marked Andantino, as the fourth movement. This accounts for the quintet’s unusual five-movement design as well as its nickname.

Despite a few gloomy moments of minore, nothing in Schubert’s chamber music radiates so much brightness and carefree melody, or exudes such immediate charm, as the “Trout” Quintet. To Anne-Sophie Mutter, this trout “cannot have died centuries ago. It’s as fast as an arrow, vibrant and alive. Schubert expressly omits that part of the song where the trout meets its end.” Daniil Trifonov, too, sees an incredible amount of energy in this work. Yet for all its cheerfulness, it also has moments of agitation verging on violent outbursts: “There are so many accents on the page, so many sforzandi and extreme dynamic marks. The most frequent expression mark is fortepiano. And often the sound brightens into a blinding glare.” To Trifonov, Schubert’s works as a whole are among the most significant in the literature of music: “They’re so pure, so simple in structure, so forthright in expression. Even if things get much more extreme in the late piano sonatas, here Schubert is already thinking in long phrases, in seemingly endless lines of development that must be made to cohere.”

This aspect also applies to the Notturno D 897. It was written in 1827 at the same time as the late piano trios, perhaps as a rejected slow movement for the Trio in B flat major D 898. Schubert scholars have not dealt kindly with it. Alfred Einstein, for example, found it “singularly empty”, which would be perfectly apt if it were not derogatory. It is precisely this atmosphere that impresses Daniil Trifonov: “In many respects, the way Schubert experimented with sounds in the ultra-high piano register was an acoustical adventure in an age that had barely discovered this progressive use of the pedal. He specifically writes con pedale, and it is not only in its arpeggios that the entire work somewhat foreshadows Impressionism.” Anne-Sophie Mutter also notices the sometimes extreme realms of sound and boldness of timbre: “That’s precisely why we decided to dispense with vibrato when the theme recurs at the end with harp arpeggios in the piano. It imparts tranquillity to the entire piece, as if one were gazing across the measureless sea.”

The two Schubert arrangements by Jascha Heifetz and Mischa Elman have been lightly “re-arranged” by Anne-Sophie Mutter and Daniil Trifonov. Heifetz added Ave Maria to his repertoire in 1917 and played it no fewer than 211 times by 1950. Anne-Sophie Mutter considers it “a fine arrangement that I’ve included among my encore numbers for years”. Indeed, she believes altogether that these little pieces should not be held in low esteem: “It’s a literature all of its own with a quite special style. The lovely arrangement of Ständchen, for example, lends wonderful expression to the isolation, darkness and melancholy that weigh upon this song – even if Daniil, Franz Liszt and I have given the arrangers a bit of a help to make the original stand out a bit better.”

Oswald Beaujean, September 2017

Translation: J. Bradford Robinson