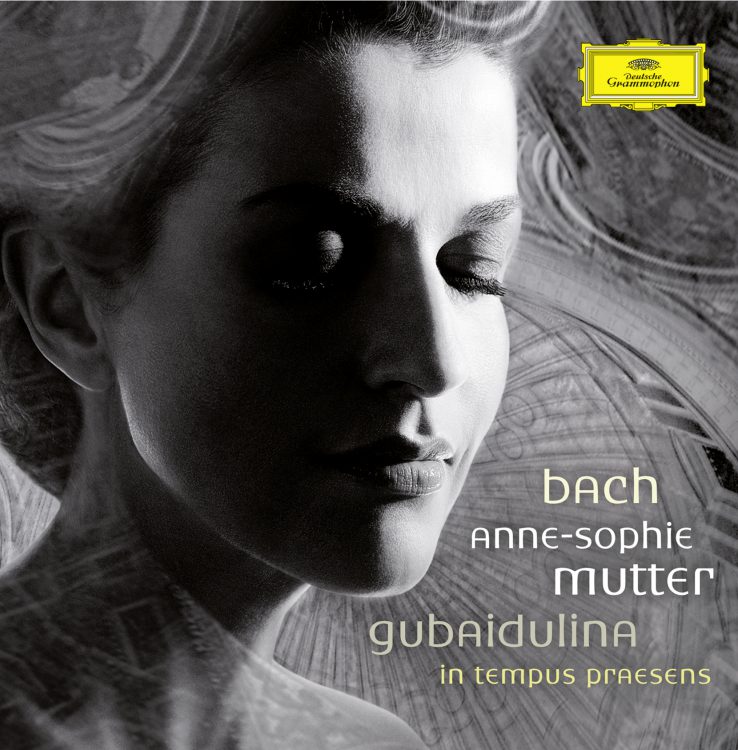

Written in 2006 – 07, the violin concerto is the first piece by the Russian composer that Anne-Sophie Mutter has recorded. “I knew about Paul Sacher’s commission and have been waiting patiently for ‘my’ work since the 1980s. Not that this means that I haven’t taken every opportunity to follow Sofia Gubaidulina’s career very closely, although I got to know her personally only just before the first orchestral rehearsal in Berlin, when I played In tempus praesens for her. It was a very moving moment for me. She is undoubtedly one of the most fascinating of all composers, in that every note reveals such great depths of emotion. She truly lives to compose and doesn’t compose to live.”

Sofia and (Anne-)Sophie – the similarity between the two names inspired Gubaidulina. “During this whole time, I was accompanied by the figure of Sophia – divine wisdom. It was all entirely spontaneous: our names are the same – it was this that provided the basis for this association,” the composer explains. For Gubaidulina, Sophia is the figure revered by orthodox Christianity, the personification of wisdom who has laid the foundations for all creativity and intellectual effort in the history of creation, preparing the way for all that develops organically in the world. She is the fountainhead of art and of the artist’s engagement with the lighter and darker sides of human existence.

Formally and musically, Gubaidulina’s five-part concerto unfolds in two different directions. On the one hand, it obeys the impassioned desire to develop, spreading out in the form of a fan with an exponentially increased number of sounds, pushing forward into the instruments’ highest registers, which represent heaven, while also exploring the deepest regions of hell through the use of trombones, tuba and contrabassoon. At the same time, however, the work expresses the utter necessity of reducing this whole creative variety to a single sound once again, its unison implying divine unity, which on a concrete level takes place during the transition from the fourth to the fifth episode.

Anne-Sophie Mutter finds this passage particularly inspired. The violin attempts to break free from the fate motif in the orchestra, an idea implacably repeated and intensified in the 40 bars leading up to the cadenza: “It rises to a tremendous climax and to the work’s most decisive moment, which takes the form of a portentous whole bar’s rest from which the beseeching solo cadenza finally breaks away.” For the soloist, a particularly magnificent moment is the burial scene that recalls the Russian Orthodox Church and that is painted in sombre colours by the cellos and violas. “Towards the end, the Wagner tubas soar aloft in an enormously powerful gesture of revolt, unleashing a torrent of ecstasy, as if Brünnhilde were riding towards us.

The result is a triumph over fate. The final bars float away, reaching the ultimate heights, in a wonderfully positive spirit, while the lower strings again recall the earlier mood of sombreness, the struggle between light and dark that is typical of In tempus praesens. I hear in it Bach’s final chorale, Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit. The work dies away in this spiritual mood on a high F sharp.”

Just as the traditional proportions of the golden section are fundamental to the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, so Sofia Gubaidulina, too, aspires to the ideal of architectural proportions in her music, seeking to impose on her works a regular structure that in turn determines the relations between their individual formal sections. In this violin concerto great importance is attached to numerology, the composer seeking what she herself terms “the rhythm of form”. The solo violin is spirited away to “heavenly spheres”, acquiring through its sonorities a unique position in the work, which is stressed by the fact that the piece’s orchestral resources include neither first nor second violins. For Anne-Sophie Mutter, this is remarkable: “The solo violin never Stopps speaking but emerges from the dialogue with the orchestra. At the same time, however, the orchestra shadows it, ist thematic material being echoed in the violas and cellos. Such close integration between soloist and orchestra increases the work’s dramatic character and results in its oppressive feel, something apparent from the solo violin’s very first outburst, which is both accusatory and psalmodic in tone. There isn’t a single moment in which we are able to take a deep breath.”

In the course of her career, Anne-Sophie Mutter has premiered a whole series of contemporary violin concertos, but she regards Sofia Gubaidulina’s contribution to the medium as unique: “I am not exaggerating when I describe it as affording me the greatest experience I have had until now with a modern score. It is a work of tremendous emotional intensity.” The present world-premiere recording of Gubaidulina’s concerto, which received its first performance in Lucerne in 2007, appears here in a coupling with Bach’s Violin Concertos BWV 1041 and 1042. This is the second time that Anne-Sophie Mutter has recorded these works – the first was some 20 years ago – and her view of Bach has changed in the meantime: “The change in my attitude to Bach is also related, of course, to the exciting findings of period performance practice, although I myself have problems with specialization of any kind – the doctrines that are developed from it and that prevent one from asking questions work against any sense of free inspiration in art. And authenticity is in any case a Utopian notion. All of us perform Bach’s music from the standpoint of the 21st century.”

Clarity and lightness should be achieved through sparing use of vibrato and through flowing speeds. In the fast movements in particular, Anne-Sophie Mutter feels that it is especially important to adopt a sensitive approach to the original phrasing: “Can one achieve this phrasing with a modern bow? The answer is an unequivocal no. That is why I was previously able to realize only some of these phrase markings using a modern bow – although they were technically still just about possible, they did not sound right. On this occasion both I myself and the orchestral players all used copies of Baroque bows and in this way achieved a very different tonal concept.” Conversely, Anne-Sophie Mutter decided against using gut strings: “I am sure that Bach’s musical ideal was free from the problems of poor intonation and the other shortcomings associated with gut strings. For 20 years I have been using a soft wound A-string that offers more warmth and in certain ways comes closer to the aesthetic of the fully rounded tone that is associated with gut strings.”

In thinking about Bach, Anne-Sophie Mutter again recalls his “spiritual descendants”: “For me, one of the most beautiful of all Baroque quotations has a certain spiritual association with the concerto by Gubaidulina. I am thinking of the end of Alban Berg’s concerto, with the wonderful Bach chorale that is quoted there. Both works ultimately convey a very real sense of hope.”

Selke Harten-Strehk

May 2008